Plant Science &

Conservation

Garden Stories

Why a pretty spring wildflower is so difficult to grow

Pondering the Prairie Series

The lovely sunny orange blooms of hoary puccoon (Lithospermum canescens) that spark color in the dormant prairie remnants of early spring are sought by everyone trying to recreate or restore prairies. However, this pretty little spring wildflower has proved difficult to establish in prairie restorations. It’s not that this species is rare. In fact, it occurs abundantly in high-quality remnants of natural prairie. Yet, it is legendary for putting up a fight for those of us who try to establish it into new prairie plantings. Not only does it produce few viable seeds, but even if you are able to germinate the seeds and establish a few plants, there is a good chance it will show little recruitment over the years and remain a few plants. We are beginning to understand why that is, which makes for an interesting story.

Lithospermum canescens

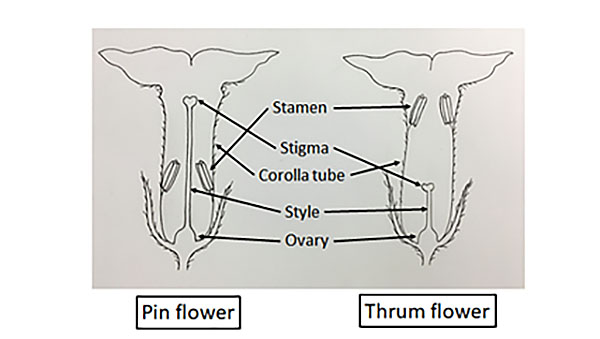

One unique feature of L. canescens is that it has two different flower types. These types are distinguished by the length of the styles (central stalk of the flower’s ovary that support the stigma, which receives pollen) in the throat of the corolla (cluster of fused petals) and the position of the stamens (male structure of a flower that produces pollen). Flowers with long styles that elevate the stigma above the stamens are called pin flowers, and flowers with short styles that support the stigma below the stamens are called thrum flowers. In addition to the length of the styles, the stamens are either attached to the throat of the corolla up high in thrum flowers or down low in pin flowers. They are essentially the reciprocal of each other (see diagram). Individual plants can produce either pin flowers or thrum flowers. The production of two different flower types is thought to be an evolutionary strategy for plants that have self- incompatible pollination, such as L. canescens. To be incompatible means a stigma will not accept pollen produced from stamens on the same plant. Only pollen from stamens of a different plant will fertilize the stigma, which ensures cross pollination. Only pollen from thrum flowers is compatible with the stigmas of pin flowers and vice versa. Therefore, both pin and thrum flowers must be present in fairly equal proportions in a population in order to maximize successful seed production and a healthy recruitment of individuals in the population.

Diagram of a longitudinal section through both types of L. canescens flowers, showing the difference in structure.

Another issue that adds to the difficulty of growing this species in prairie restorations is the fact that L. canescens produces very few viable seeds compared to the number of flowers produced, even if both flower types are present. Its flowers open sequentially as the inflorescence (group of flowers) expands throughout the blooming period. The first flowers to open and are successfully pollinated are the ones that will produce seeds, when resources are plentiful. Since energy costs to produce seeds are high, flowers that open subsequently are often aborted, even if successfully pollinated.

In addition to specific pollination requirements and limited seed production, the establishment of this species in prairie restorations may be compromised because of the close association the roots of L. canescens have with mycorrhizal fungi. The majority of plants on earth engage in this beneficial relationship. A special group of fungi called mycorrhizae colonize the roots of plants to the benefit of both species—the fungi, which cannot produce its own sugars, receives it from plants, which can produce sugars through photosynthesis and, the fine, thread-like fungal hyphae (primary body of the soil-living fungus) absorbs nutrients and water for the plant whose root system cannot penetrate the soil as efficiently as the fungi. It is a win-win for both organisms. If this association is obligate for the plant—which may be the case for L. canescens —it will struggle in environments where the association is lacking. In young prairie restorations, these associations may be poorly developed.