Plant Science & Conservation

Garden Stories

Plant Patterns: Where Beauty Meets Function

Ever been captivated by the spiral of a sunflower or the one-of-a-kind stripes on a zebra? Our brains are natural pattern detectors, wired by evolution to appreciate structure in chaos. Decoding patterns helps us navigate the world—it’s how we recognize faces, understand language, and learn new skills.

For scientists, patterns are also clues that something deeper is at work.

“Nature is inherently random, so patterns indicate either selective pressures or a predictable process, hence something worth exploring more,” said Jeremie Fant, Ph.D., a conservation scientist at the Negaunee Institute for Plant Conservation Science and Action at the Chicago Botanic Garden. “Evolution has a way of weeding out what’s not useful.”

Patterns in plants—from microscopic leaf veins to elaborate petal designs—are unique expressions of a plant’s genetic makeup that may reveal what it needs to thrive.

These biological patterns run deep. The same molecular processes that shape human fingerprints also generate a leopard’s spots or polka dots on a flower—a phenomenon first introduced in 1952 by codebreaker Alan Turing, who, among his many achievements, theorized how chemistry on the tiniest scale can choreograph nature’s most intricate designs.

The biology behind the beauty

Some plant patterns have clear biological purposes—helping the plant grow, reproduce, or adapt. Others remain a mystery, inviting further discovery. Here are a few common reasons plants have patterns.

1. Guiding pollinators

Striped petals might look decorative to us, but to an insect, they are like runway landing strips, guiding them to pollen and nectar.

“Bees need a place to land—and they like to know where to go,” Dr. Fant explained. “By contrast, flowers that rely on hovering pollinators, like moths or hummingbirds, have different visual cues that guide their tongues to the flower’s entrance like a bullseye for a dart.”

Some orchids take pollinator pattern-play a step further, mimicking the appearance of female insects to attract hopeful mates. The butterfly orchid (Psychopsis papilio), for instance, is shaped, spotted, and named for its pollinator.

Look for pollinator-attracting patterns at the Garden:

Check for the speckled petals of the Michigan lily (Lilium michiganense) in the Dixon Prairie in July.

2. Efficient growth

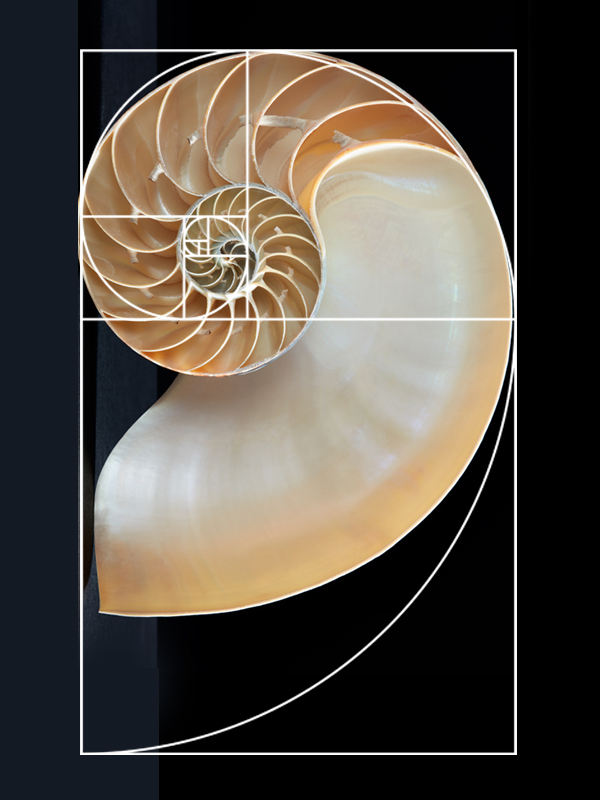

The spiraling form of the scaly tree fern (Cyathea cooperi) isn't just elegant—it’s functional. Each new frond unfurls at a specific angle, ensuring each part gets sunlight without overlapping with the others.

This growth pattern follows the Fibonacci sequence—a common mathematical pattern found in nature that, for the fern, allows for compact and efficient growth. Just like bees—who build their honeycomb in hexagon shapes to maximize storage space using minimal wax—this plant makes the most of space and energy as it expands.

Look for Fibonacci growth patterns at the Garden:

See the spiral in action in the scaly tree fern in the Krehbiel Gallery.

3. Protection

The spotted bark of the American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) is more than a visual quirk—it’s part of the tree’s growth process. As the trunk expands, it sheds older bark in patchy layers, possibly reducing disease, pests, or lichen buildup while exposing younger, more photosynthetic tissue underneath. The result? A hardy tree that can live for centuries.

Look for protective patterns at the Garden:

American sycamores can be found near the Lavin Plant Evaluation Garden as you walk along the path toward Evening Island.

4. Variegation & cultivation

Not all plant patterns serve a purpose. Some are ornamental, even accidental—especially those found on leaves. While many of nature’s striking designs appear on petals, patterned foliage stands out as a rarity.

Variegated leaves, like the Monstera albo (Monstera deliciosa 'Albo Borsigiana') or the bright spots of Bethlehem sage (Pulmonaria saccharata), may result from genetic mutations or even disease. These aesthetic traits can come at a cost: variegation reduces the plant’s ability to photosynthesize. Beautiful? Absolutely. Beneficial? Not always.

Humans also play a role in what patterns persist through generations of propagation. “We’ve always chosen favorites—compact plants with showy flowers or bold, symmetrical leaves,” said Fant. “But what we love in a garden or houseplant might not help a plant survive in the wild.”

Look for variegation at the Garden:

Keep an eye out for Pink Splash caladium (Caladium 'Pink Splash') in the Welcome Plaza or Bethlehem sage in the English Walled Garden.

Discover your surroundings anew

Patterns are everywhere—from tiny snail shells to big drifting clouds. When we pause to notice, nature reveals a hidden language.

“The more you look, the more you see,” said Fant. “And once you see a pattern, the next question is: Why is it there? ”

Discover Patterned by Nature, the Garden's summer exhibition, where playfully planted gardens and nature-inspired art celebrate our universal attraction to patterns.