Plants & Gardening

Garden Stories

The unsung life of a trailblazing plant collector

English | Spanish

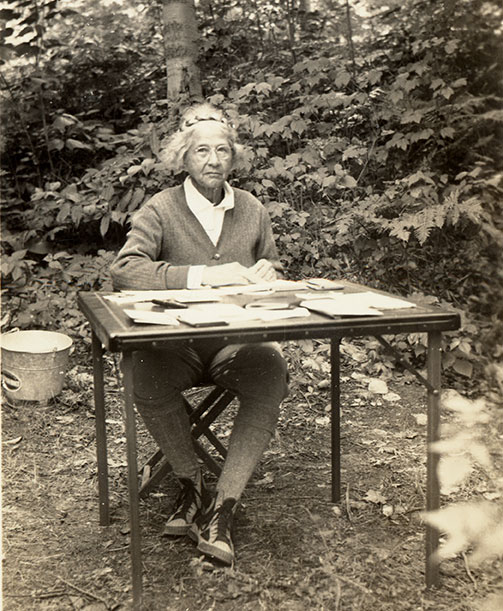

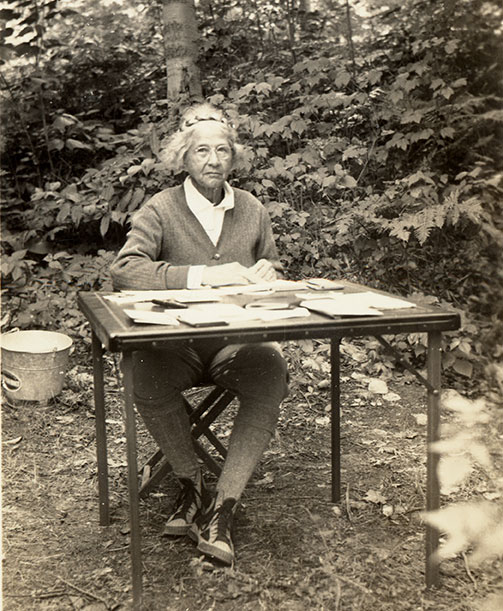

I would like to honor a great figure in the world of plants. Her name was Ynes Enriquetta Julietta Mexia.

Ynes Enriquetta Julietta Mexia

Mexia was one of the most accomplished botanical explorers and plant collectors of her time. Her story is not widely known but deserves recognition. An American of Mexican descent, Mexia embodies the purpose of National Hispanic Heritage Month, which runs through October 15. The federally recognized month honors the “achievements and contributions of Hispanic American champions who have inspired others to achieve success.”

When I was honored to be part of an international plant collecting trip initiative for the Chicago Botanic Garden, I did some research about plant explorers, and I came across Mexia’s name and work. I felt the need to look up to someone with a similar life experience such as mine, and Mexia was the perfect example of determination and intrepidity.

Today, there are more women and people of color exploring the natural world and embracing the outdoors, but Ynes Mexia was a trailblazer. She was one of the first female plant explorers in a world where women were limited to only a few career choices, and she made her mark at a time when the fields of botany and plant collecting were dominated by men.

Daughter of a Mexican diplomat father and an American woman, Mexia was born in 1870 in Washington, D.C., where her father was stationed. She was a quiet girl with a passion for reading. Despite her privileged background, Mexia experienced adversity. Her parents divorced when she was just 9 years old, and she was sent to a private boarding school. She finished her studies and considered entering a convent. But by that time, her dying father had asked her to take over the family ranch in Mexico before the Mexican Revolution started.

Mexia married twice. Her first husband died after battling a long illness, and the second husband brought ruin to the ranch. After all this hardship, she suffered a breakdown and decided to move to San Francisco, where she sought medical help. At her psychiatrist’s encouragement, she joined environmental groups in California. The shy girl she once was became an outspoken advocate of the environment, going on excursions and enjoying the outdoors. When I think about her, I dare say she found purpose and meaning in life again through nature. The calming influence of nature is well known, as well as the therapeutic effect it has on individuals and communities.

In California, Mexia pursued an education in the natural sciences at age 51, and she discovered botany. Back then, gardening was viewed as an acceptable educational path for women. With the right connections, she went on her first plant expedition to Sinaloa, Mexico, with the leading American botanist Roxanna Ferris from Stanford University. There is not enough documentation to know exactly what happened during that trip, but Mexia realized she would be more productive if she went on her own.

She was able to obtain funding for more trips, traveling to Alaska and most of the Americas. One of her most successful trips was in Mexico, where, despite suffering a terrible accident—she fell down a cliff and broke her arm and a few ribs—she collected about 500 plant specimens. She gained recognition from botanical institutions that then sponsored more expeditions.

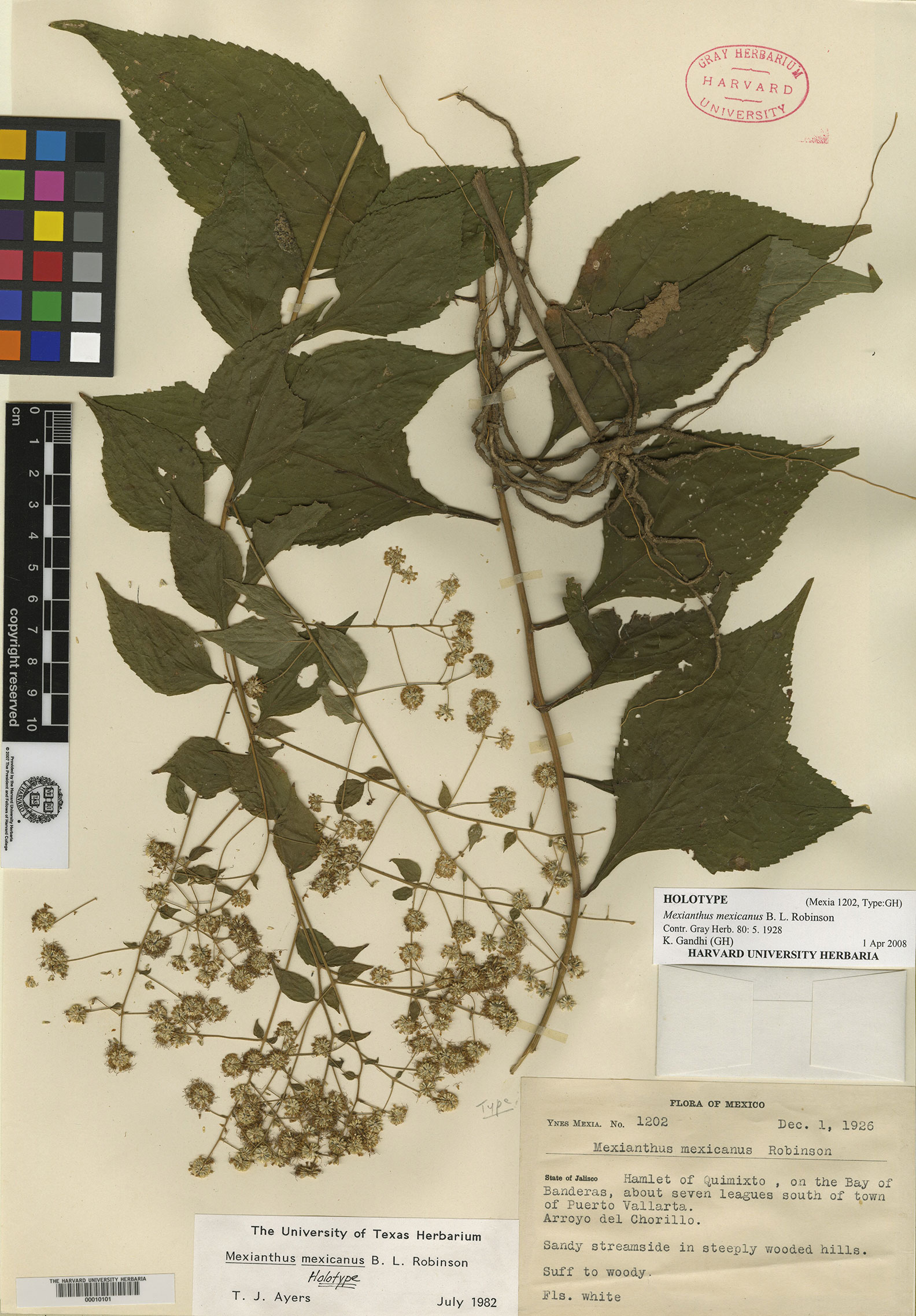

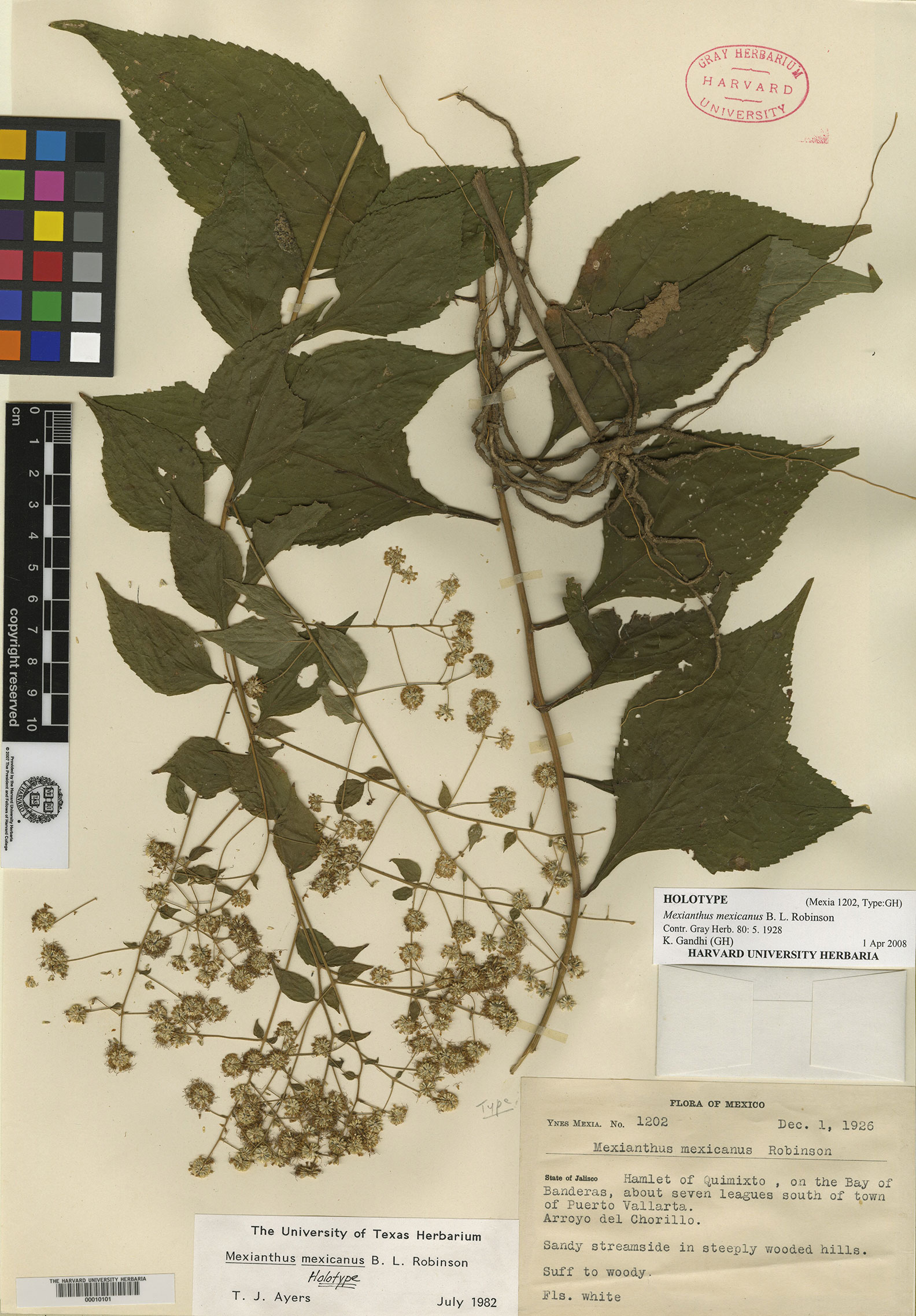

For the next 12 years, Mexia collected around 150,000 plants. Mexianthus was the first plant genus named in her honor. I’d like to believe that as a plant collector and the daughter of a diplomat, she was respectful of the idiosyncrasies and customs of the places she visited. One way to show respect was her ability to connect with the locals in their primary language, Spanish. I imagine her showing them how to collect herbarium vouchers—dried and pressed plants that are recorded and kept in proper storage. There were so many of them!

However, Mexia didn’t do it alone. While her strength was collecting, she found help in Nina Floy Bracelin, an American botanist and illustrator who inventoried Mexia’s collection, and prepared and labeled the specimens for their categorization. This is a vital part of documenting any plant exploration. Interest and curiosity, funding, exploring while engaged with the locals, good communication, inventories, and notes—I would say this makes for excellent diplomatic teamwork.

Ynes Enriquetta Julietta Mexia died on July 12, 1938, at age 68 of lung cancer. In her will, she left funds to the California Academy of Sciences for the employment of Bracelin, her collections manager.

Gabriela Rocha Alvarez is the plant recorder at the Chicago Botanic Garden.

Photo credits: Ynés Mexía © California Academy of Sciences

Gabriela Rocha Alvarez

Mexianthus mexicanus

Me gustaría hacer un homenaje a una gran figura en el mundo de las plantas. Su nombre era Ynés Enriquetta Julietta Mexía.

Ynes Enriquetta Julietta Mexia

Mexía fue una de las exploradoras botánicas y coleccionistas de plantas más consumadas de su tiempo. Su historia no es ampliamente conocida, pero merece reconocimiento. Una estadounidense de ascendencia mexicana, Mexía encarna el propósito del Mes Nacional de la Herencia Hispana, que se extiende hasta el 15 de octubre. El mes que reconoce y honra federalmente los "logros y contribuciones de los campeones hispanoamericanos que han inspirado a otros a alcanzar el éxito".

Cuando tuve el honor de ser parte de una iniciativa internacional de viaje de recolección de plantas para el Jardín Botánico de Chicago, investigué un poco sobre los exploradores de plantas, y me topé con el nombre y trabajo de Mexía. Sentí la necesidad de admirar a alguien con una experiencia de vida similar a la mía, y Mexía fue el ejemplo perfecto de determinación y osadía.

Hoy en día, hay más mujeres y personas de color que exploran el mundo natural y acogen actividades al aire libre, pero Ynés Mexía fue una pionera. Fue una de las primeras exploradoras de plantas en un mundo donde a las mujeres se les limitaba a unas pocas opciones de carrera, y ella dejó su huella en un momento en que los campos de la botánica y la recolección de plantas estaban dominados solo por hombres.

Mexía nació en 1870 en Washington, D.C. donde su padre trabajaba. Hija de un padre diplomático mexicano y una mujer estadounidense. Era una niña tranquila y apasionada por la lectura. A pesar de su origen privilegiado, Mexía experimentó adversidades. Sus padres se divorciaron cuando ella tenía solo 9 años, y fue enviada a un internado privado. Terminó sus estudios y consideró entrar a un convento. Pero para ese entonces, su padre moribundo le había pedido que se hiciera cargo del rancho familiar en México antes de que comenzara la Revolución Mexicana.

Mexía se casó dos veces. Su primer esposo murió después de una larga enfermedad, y el segundo trajo ruina al rancho. Después de todas estas dificultades, sufrió una crisis y decidió mudarse a San Francisco donde buscó ayuda médica. Con el incentivo y ánimo de su psiquiatra, se unió a grupos ambientalistas en California. La niña tímida que alguna vez fue se convirtió en una defensora abierta del medio ambiente, iba a excursiones y disfrutaba del aire libre. Cuando pienso en ella, me atrevo a decir que encontró nuevamente propósito y significado en la vida a través de la naturaleza. La influencia tranquilizante de la naturaleza es bien conocida, así como el efecto terapéutico que tiene en individuos y comunidades.

Ahí en California, Mexía siguió con una educación en ciencias naturales a los ya 51 años, y descubrió la botánica. En aquel entonces, la jardinería era vista como un camino educativo aceptable para las mujeres. Con las conexiones correctas, ella realizó su primera expedición de plantas a Sinaloa, México, con la destacada botánica estadounidense Roxanna Ferris de la Universidad de Stanford. No hay suficientes registros para saber exactamente lo que sucedió durante ese viaje, pero Mexía se dio cuenta de que sería más productiva si fuera por su cuenta.

Pudo obtener fondos para más viajes, viajando a Alaska y la mayor parte del continente Americano. Uno de sus viajes más exitosos fue en México, donde, a pesar de sufrir un terrible accidente -se cayó en un acantilado y se rompió el brazo y algunas costillas- recolectó unos 500 ejemplares de plantas. Obtuvo el reconocimiento de instituciones botánicas que luego patrocinaron más expediciones.

Durante los siguientes 12 años, Mexía recolectó alrededor de 150,000 plantas. Mexianthus fue el primer género de plantas nombrado en su honor. Me gustaría creer que como recolectora de plantas e hija de un diplomático, ella era respetuosa con la idiosincrasia y las costumbres de los lugares que visitaba. Una forma de mostrar respeto, fue su capacidad de acercarse a los lugareños en su idioma, el español. Me imagino a ella enseñándoles cómo recolectar herbario -plantas secas y prensadas que se registran y se guardan en una bóveda. ¡Había tantos de ellos!

Sin embargo, Mexía no lo hizo sola. Mientras su fortaleza era coleccionar, encontró ayuda en Nina Floy Bracelin, una botánica e ilustradora estadounidense que hizo un inventario de la colección de Mexía, y preparó y etiquetó los especímenes para su categorización. Esta es una parte vital de la documentación de cualquier exploración de plantas. Interés y curiosidad, financiamiento, explorando mientras se relaciona con los lugareños, buena comunicación, inventarios y notas, diría que todo esto lo convierte en un excelente trabajo diplomático en equipo. Ynés Enriquetta Julietta Mexía murió el 12 de julio de 1938, a los 68 años de cáncer de pulmón. En su testamento, dejó financiamiento a la Academia de Ciencias de California para el empleo de Bracelin, su directora de colecciones.

Traducido del inglés por Gabriela Rocha Alvarez

Gabriela Rocha Alvarez

Mexianthus mexicanus