Plant Science & Conservation

Garden Stories

Weaving the Landscape Back to Life

In a sunny patch at the Chicago Botanic Garden, a single bee balm (Monarda fistulosa) stretches toward the sky. A long-lost visitor lands: a rusty patched bumble bee (Bombus affinis), fuzzy and endangered, unseen here before. The rare sighting is a bright thread in a much larger tapestry being rewoven across the region.

Once one of the most common bumble bees in the Midwest, the rusty patched population has declined by 90 percent in the last decade. Its reappearance at the Garden isn’t an accident. For years, our ecologists have been restoring native plants to the landscape, carefully stitching back the connections that support pollinators, wildlife, and people alike.

Bee balm, the flower that drew the bee that day, is one of many resilient native species helping to reweave balance. Its tubular blossoms attract hummingbirds and butterflies; its roots anchor the soil and better its ability to absorb stormwater; its seeds sustain birds through winter. Each plant plays a part in strengthening the landscape.

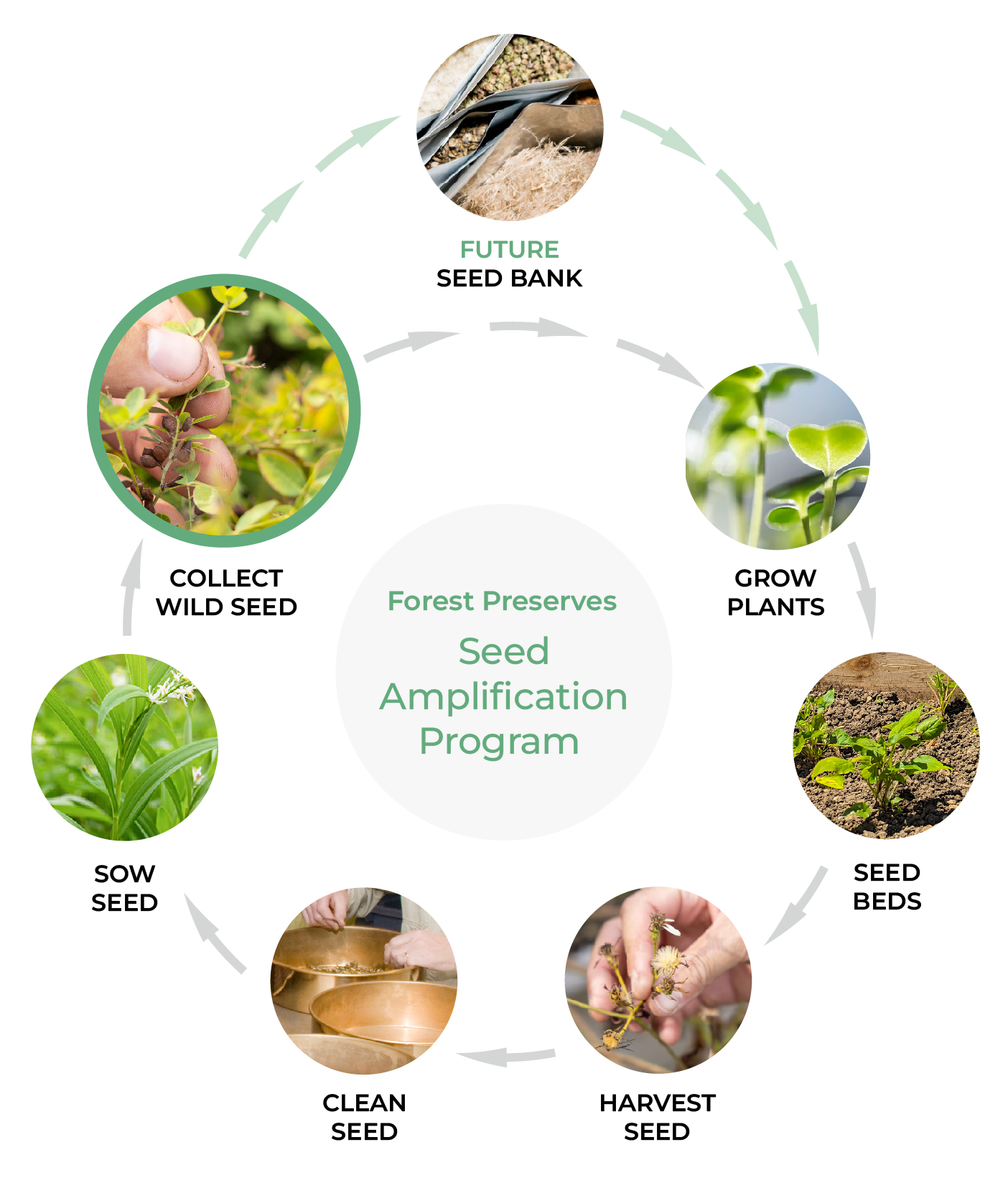

Program Manager Molly Marz describes the goals of the Seed Amplification Program.

“It’s been intense,” said Molly Marz, the manager of the Seed Amplification Program. “It’s gone really fast, but I think we’re really proud of the work that we’ve been able to do.”

At the native seed nurseries, staff work in rhythm with the plants, collecting seed only when each plant is ready. The process is intensive, but so is weaving anything meant to last.

“Sometimes on a frustrating day where things don’t go the right way, I just think about each seed going on and living a healthy life as a new plant in the forest preserves somewhere,” said Noah Hornak, technician at the native seed nursery. “It feels like we’re doing something meaningful, doing the best we can.”

Each new bloom draws pollinators back; each native plant threads a pattern of resilience across the landscape. From bee balm (Monarda fistulosa) to fields of rare purple milkweed (Asclepias purpurascens), every native seed sown adds another row to the tapestry of recovery. Thread by thread, patient hands and resilient roots are weaving the landscape back to life.