News

Garden Stories

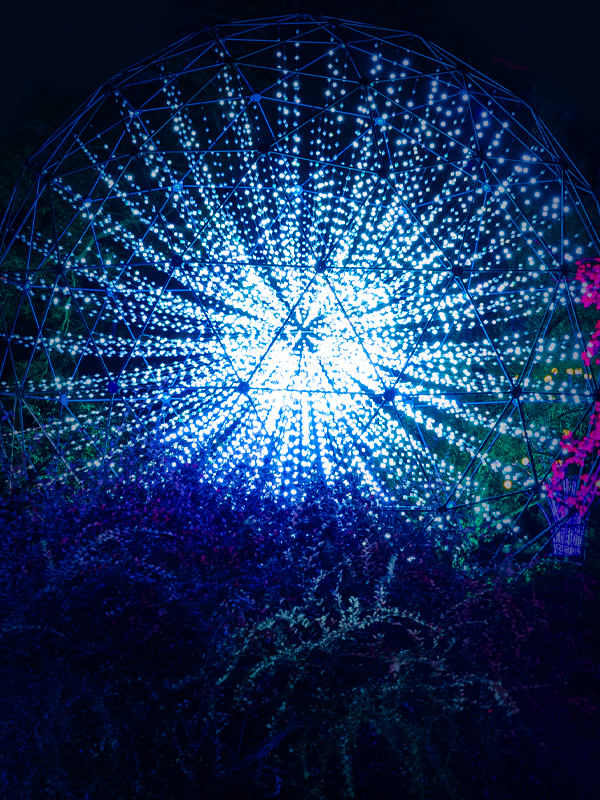

A Cosmic Portal in the Garden

What do you hope people feel when they experience Singularity?

All of our works, including Singularity, are meant to transport people out of the everyday grind for a while—to sit there and just go, wow. It’s about rediscovering a sense of childlike wonder, forgetting who and where you are for a moment, and being drawn into this glowing, shifting thing. It’s a chance to take a breath.

Why bring Singularity to a botanic garden?

I love the contrast between the digital, geometric nature of what we do and the organic beauty of nature. But it’s also the same impulse. I can stare at a tree for hours and lose myself in it. Winter light festivals have that same effect: they help people step out of themselves and reconnect with a bigger whole.

Was there an “aha moment” that inspired the installation?

During early tests, a sequence happened where all the lights expanded outward and then collapsed in on themselves, and it was fantastic. For me, it instantly evoked black holes, infinite compression. That was the spark. From there, it became a matter of figuring out how to build it. We worked with a small UK company that makes geodesic domes, and they’d never done a full sphere before. We said, “Let’s try it.” It worked and didn’t fall down! Every version since has been a learning curve. It took years to arrive at where it is now.

What keeps you going through challenging moments in the creative process?

Honestly, it’s a slog sometimes. I’ve flicked the switch for the first time and all the fuses blew. A sea of chaos. But then you fix all the short circuits, and when you finally power it up, that first wow moment happens when it all comes alive. That’s what I live for. I’m as much an audience member as anyone else. I often have a vision burning a hole in my brain until I can manifest it, and the process rarely goes in a straight line. But those moments of discovery make it all worth it.

What’s it like seeing people encounter Singularity for the first time?

When it was shown in London, people would do a double take. It takes a moment to register. It’s a sphere, yes, but also a whole volume of light with a glowing core more than 8 meters, or 26 feet, across. Watching families and people respond to it outside of art galleries, out in the world, in an open, honest way—that’s what art should be.

You have an unconventional path to this kind of work. How did you get here?

My background is in mechanical engineering, interactive design, and art. I spent years trying to make immersive experiences on screens, but screens are barriers—everything happens on the other side. I wanted to be inside the work. Before that, I had a few different lives, including sailing solo across the Atlantic, trying to find what fit. Then I discovered digital media in the mid-‘90s. I knew art; I knew computers. But I hadn't realized that you could put the two together.

Do you think people are surprised by how science, technology, and art can merge?

The most interesting ideas come from the overlaps between fields: art, science, design, technology. Whenever someone tells us an idea “can’t be done,” that’s usually when we know we’re onto something. A decade ago, people said Submergence—the predecessor to Singularity—was impossible. Now the technology’s common, but back then, when people said we couldn’t do it, we said “challenge accepted.”