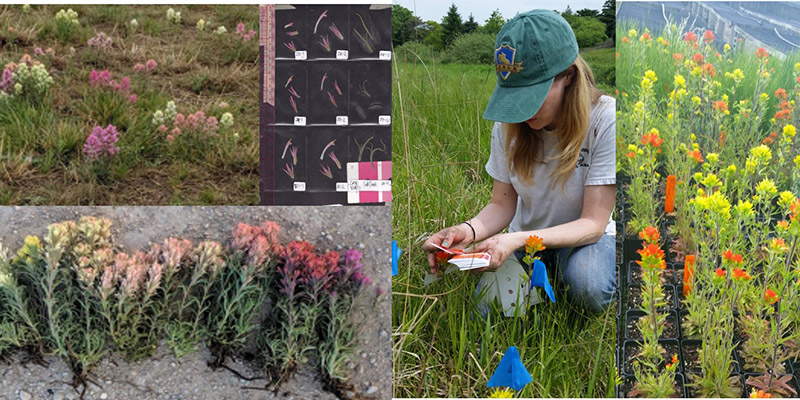

The striking diversity of floral shapes, color, and scent has captivated poets and scientist alike. However, Darwin noted that the diversity of flowering plants was almost too great to believe, something he referred to it as the “abominable mystery.” The quest to answer why we have so many flowering plants is still ongoing and has made flowers a model group to answer important questions about speciation. One particularly challenging aspect of the mystery is how new forms arise and spread. Given flowers’ specialized structure, modifications can result in not attracting the right pollinator, or no pollination at all. These individuals will be less successful than others and produce fewer seed, hence favoring the more common form. For this reason, variation in floral shape, color, or scent within a population is often rare, but still can occur. When we see variation in floral forms within a population, this indicates that there is some dynamic evolutionary process in play. The hemiparasitic genus Castilleja has more than 200 species in North America, with multiple shifts in floral color and form. In this group, there are a number of species we are studying that show dramatic variation within a population. Two Midwest natives, Castilleja coccinea (Scarlet paintbrush) and C. sessiliflora (Downy paintbrush), have different color morphs being found within close proximity to each other and even within the same population. We are interested in asking what makes these different morphs successful? And is it possible that these different selective pressures would result in new species? A process known as sympatric divergence and isolation (Braum, Fant, Skogen, Wenzell, Widener, and outside collaborators).