Pollen Bank

The Chicago Botanic Garden’s Pollen Bank is a critical tool for advancing our work to prevent plant extinctions, reintroduce species into the wild, and support habitat restoration.

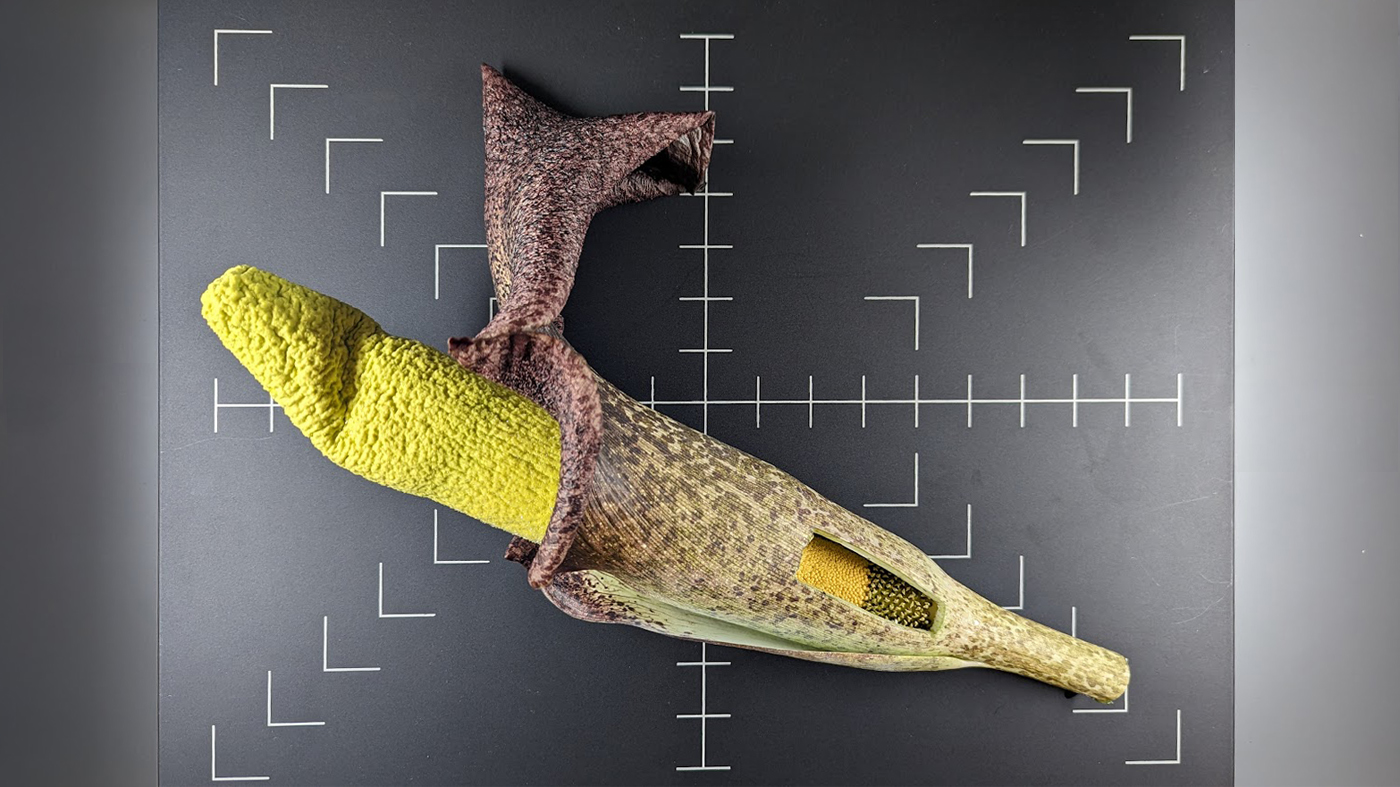

Preparing an Amorphophallus perrieri flower for pollen collection. Photo by Jeremy Foster.

Storing pollen is an efficient and effective way to protect the genetic diversity of a plant species, allowing us to preserve the unique adaptations that have helped plant species survive. The more genetic diversity we can protect, the better equipped we are to help plant species adapt to challenges from human-driven habitat loss, invasive species, and climate change.

Established in 2023, the Pollen Bank focuses on conserving oaks and orchids of the Great Lakes region and supporting the recovery of rare and endangered plants around the world.

A half-black bumblebee on a chaste tree (Vitex spp.) with pollen on its face and in the pollen sac on its hind leg. Photo by Nick Dorian.

What is pollen, and why store it?

Pollen is a fine, powdery substance produced by the male part of a plant in most species that make seeds. You may experience pollen as the invisible cause of your runny nose in the spring or the yellow powder sticking to a bumblebee visiting a flower.

Pollination occurs when an animal, wind, or water transfers pollen to the female part of a plant of the same species. If this pollen transfer is successful, the plant produces seeds that can grow into new plants.

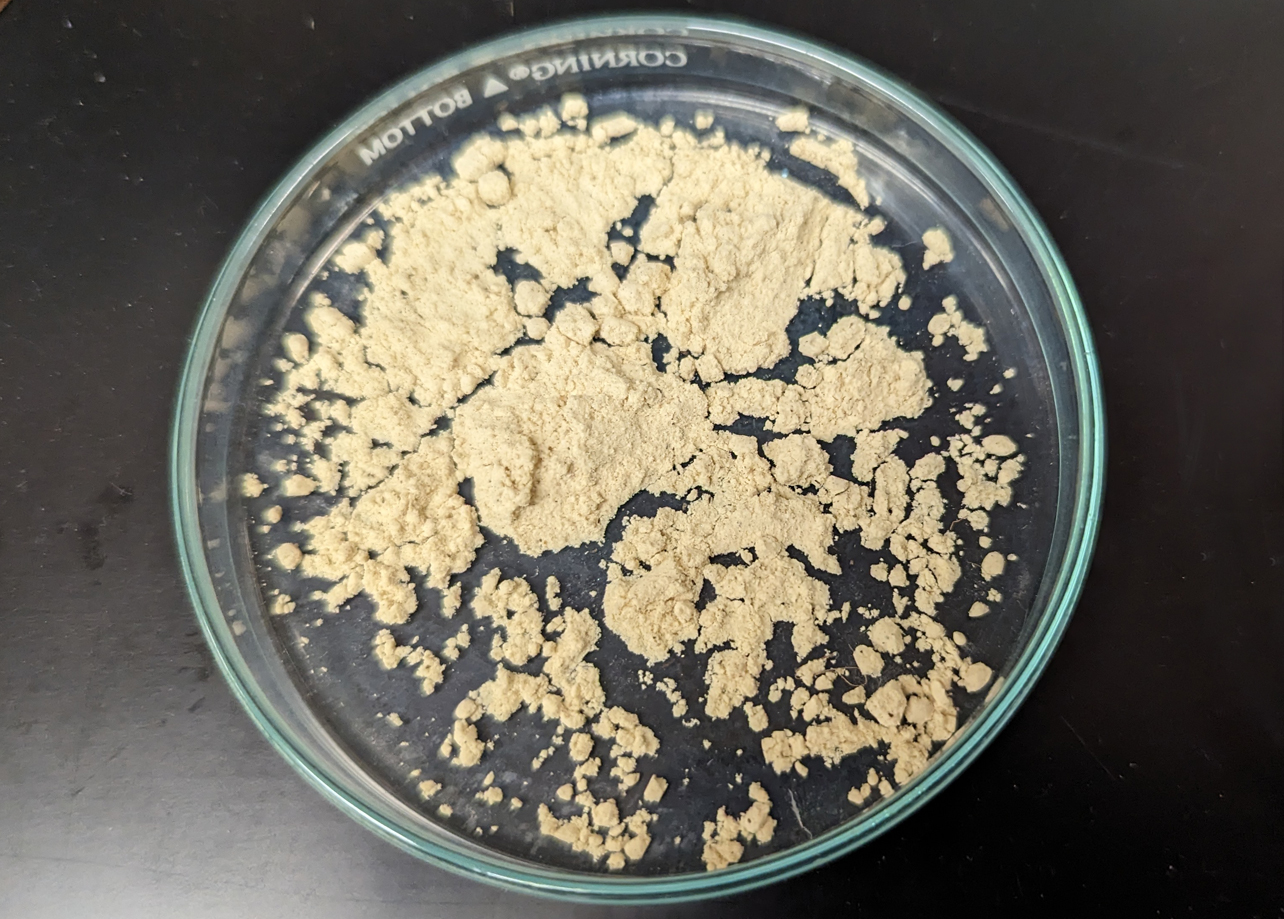

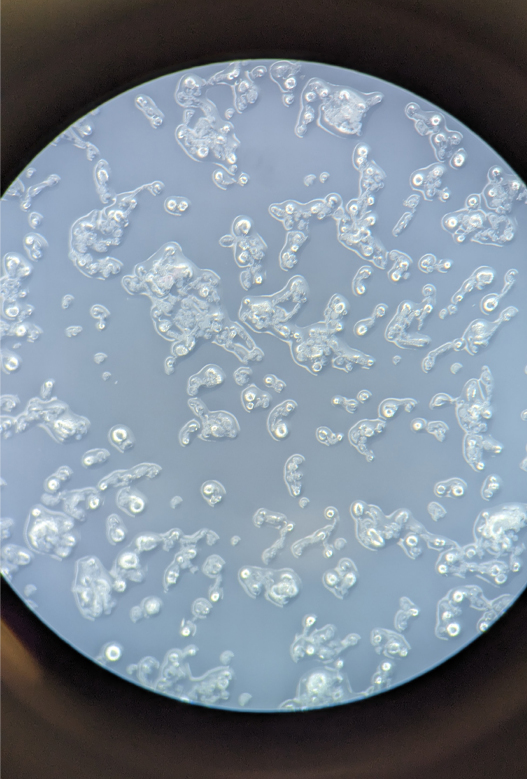

Pollen from the critically endangered Albany cycad (Encephalartos latifrons) in a Petri dish (left) and germinated under a microscope (right). Photos by Jeremy Foster.

Storing pollen is valuable when:

It isn’t possible to store seeds – Some plant species produce seeds, like acorns from oak trees, that aren’t designed to last long and won’t survive frozen in the Garden’s Seed Bank. Storing pollen allows us to preserve the genetic diversity of these species.

You need to breed plants – Our Pollen Bank is like a sperm bank for plants, storing the genetic material of just one parent. This provides the flexibility to choose the other parent and breed new plants to meet conservation goals, like increasing the genetic diversity of a species to support a reintroduction into the wild.

Space is a concern – Growing and caring for 1,000 oak trees would take a lot of land and resources. In the Pollen Bank, we can preserve the genetic diversity of 1,000 oak trees in a container the size of a shoebox for pennies a year.

Alula (Brighamia insignis) is extinct in the wild. Garden scientists are supporting reintroduction efforts that rely on the ability to store and transport pollen to breed new plants. Photo by Jeremie Fant.

Pollen banking to save rare and endangered species

Rare plant collections at botanic gardens are an important tool for preventing extinctions—but only if they are managed well.

Our scientists helped develop the plant studbook approach, a way for botanic gardens to use genetic information to manage plant breeding between institutions. By working together, botanic gardens can maintain healthy, genetically diverse plant collections that support the reintroduction of rare species to the wild. It’s a strategy that could save thousands of plant species.

But breeding plants living at different botanic gardens means transporting pollen from one plant to another plant that may be miles—or even an ocean—away. And when the pollen arrives, there’s no guarantee there will be a flower blooming to pollinate.

Pollen banking improves this process by providing the storage and testing needed to make sure breeding between botanic gardens is successful.

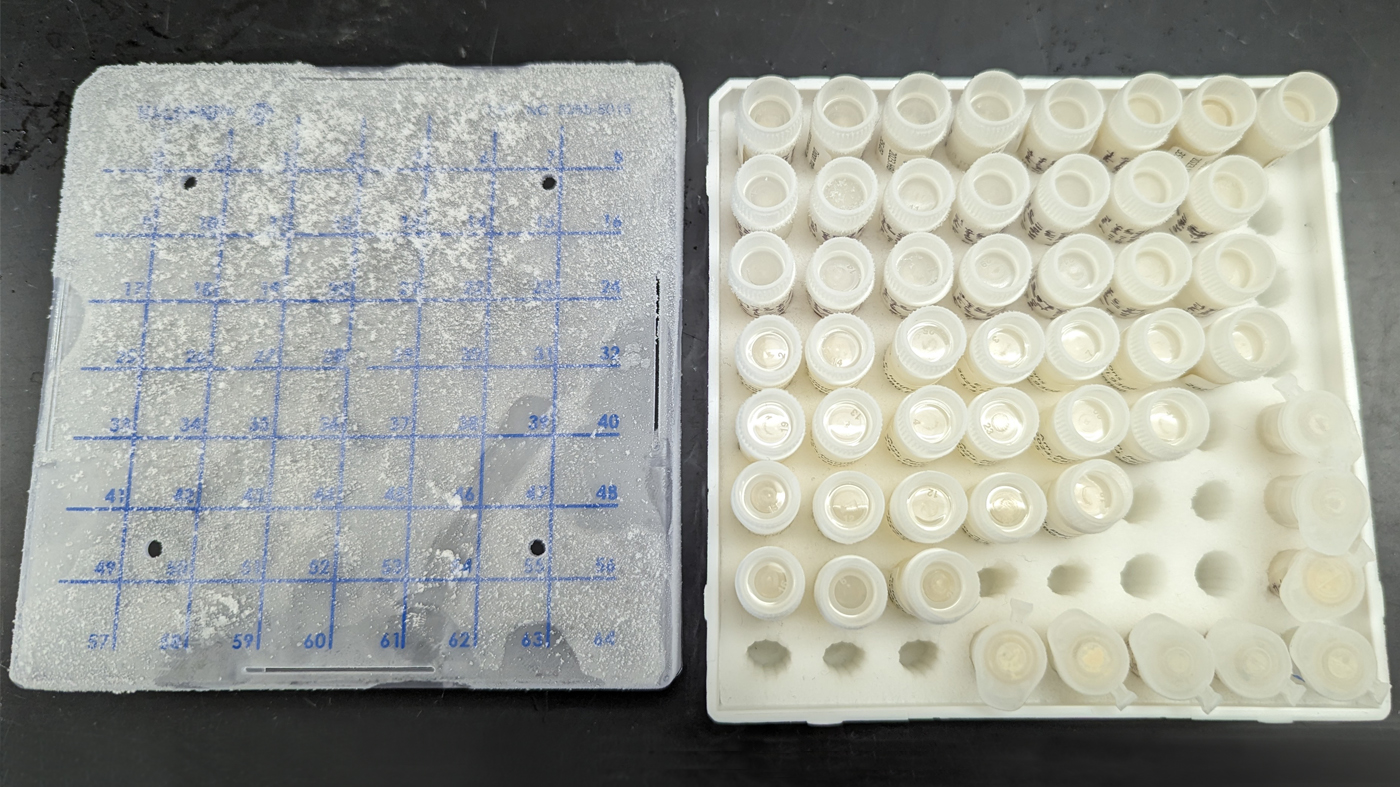

Vials of pollen from Pollen Bank’s freezer. Photo by Jeremy Foster.

How does pollen banking work?

Collecting pollen

Garden staff and knowledgeable collaborators collect pollen from plants in botanic garden collections and the wild. From the smallest orchid to the largest corpse flower, collectors harvest enough pollen to study long-term storage and pollen behavior under different drying and temperature conditions—and to use for future plant breeding.

Preparing pollen

Once the pollen is collected, we test its viability (if it can be used for breeding) in a lab at the Garden’s Plant Conservation Science Center.

Next, we dry the pollen for approximately three days to prepare it for storage. A small amount of the dried pollen is tested again for viability.

Storing pollen

After drying, the pollen is placed in vials, carefully labeled, and stored in the pollen bank at -80°C until it’s needed.

Jeremy Foster, Pollen Bank manager at the Garden, collects pollen from Amorphophallus dunnii.

Building and sharing pollen knowledge

As we grow the Pollen Bank, Garden scientists are documenting best practices for maintaining pollen collections and testing pollen viability.

Sharing this knowledge with other institutions is critical for building the pollen storage network needed to protect the genetic diversity of local species and facilitate breeding programs for rare plants in botanic garden collections.

We’re also conducting pollen research in partnership with other botanic gardens globally to advance our understanding of plant reproduction to make pollen banking even more effective.

Contact

Interested in collaborating with the Garden’s Pollen Bank? Reach out:

Jeremy Foster, Pollen Bank Manager

(847) 835-6873